Gandhi spoke no Sanskrit & Narayana Guru spoke no English when they met at Vaikom Satyagraha

When they two met in 1925, they clashed on the non-violent approach to the movement and conversion as a path to freedom for avarnas.

ROHAN MANOJ (Edited by Theres Sudeep)

PastForward is a deep research offering from ThePrint on issues from India’s modern history that continue to guide the present and determine the future. As William Faulkner famously said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Indians are now hungrier and curiouser to know what brought us to key issues of the day. Here is the link to the previous editions of PastForward on Indian history, Green Revolution, 1962 India-China war, J&K accession, caste census and Pokhran nuclear tests.

There was a bomb-drop silence in the Praja Sabha. All Trivandrum was gripped with tension as the demand for temple entry reached a fever pitch. When T.K. Madhavan got up to speak, the hearts of the more nervous members beat in their chests. The Ezhava poet, Mooloor S. Padmanabha Panicker, tactically found himself a seat at the very back of the chamber.

As it turned out, Madhavan didn’t throw a bomb, but spoke forcefully for an hour and a quarter, recalls his colleague N. Kumaran, who was there. But the fear of violence would hang over the movement before, during, and after the Vaikom Satyagraha, although the volunteers never deviated from their Gandhian approach. On one occasion, it triggered a misunderstanding between Mahatma Gandhi and Narayana Guru.

In March 1924, satyagrahis began to flock to Vaikom in the princely state of Travancore, to agitate for the public roads near the town’s Mahadeva Temple to be thrown open to avarnas, or ‘untouchables’. They came from across Kerala and far beyond; famously, a group of Sikhs arrived from Amritsar and set up a kitchen to feed the satyagrahis. To call the movement secular, though, would be misleading: Gandhi insisted that it be a Hindu affair, and alienated the Christians.

A theocratic state — its 18th-century founder, Marthanda Varma, had gifted the kingdom to the god Padmanabha, and his successors ruled as the deity’s pious servants, Padmanabha Dasa — too, made its preparations. The contested roads were put under heavy guard — the district magistrate said he wanted to prevent clashes between the satyagrahis and angry orthodox Hindus — while cases and arrest warrants appeared out of the blue against the satyagraha’s leaders, wrote K.G. Narayanan in his book Ezhava-Thiyya Charithrapathanam. The establishment had no lack of cheerleaders: “Ezhavas should be given, not temple entry, but adi (blows),” brayed one newspaper.

In any case, temple entry was still a ways off, and the movement’s immediate results were limited. The aftermath, and the tortuous path to the eventual Temple Entry Proclamation of 1936, are subject to debate.

The second in a two-part series, this article looks at what happened over the course of the Vaikom Satyagraha from March 1924 to November 1925, and what its fallout was.

Five stages of the campaign

On 30 March 1924, three men — an ‘upper-caste’ Nair, an Ezhava and a Dalit Pulaya — “dressed in khaddar uniforms and garlanded”, and followed by a crowd of “thousands” tried to use the roads. The three were arrested and sentenced to six months in prison when they refused to furnish bonds for good behaviour.

In a 1976 paper (Temple-Entry Movement in Travancore, 1860-1940), scholar Robin Jeffrey identifies five stages in the long campaign that followed. The initial phase saw a daily “ritual of satyagraha and arrest” that continued until 10 April, when the government decided to cease making arrests.

The next few months saw the police barricade the roads against the satyagrahis, who sat in front of the barricades, fasted and sang patriotic songs — and suffered attacks from “thugs” dispatched by caste Hindus. This was also the period when national leaders such as C. Rajagopalachari and E.V. Ramasamy (Periyar) visited and offered advice to the volunteers.

But this wasn’t the first time Periyar, who would be arrested twice during the campaign, was associated with the anti-caste movement in Kerala. Just the previous year, he’d been involved in an incident that exposed some of the ideological cleavages among the Ezhavas. At a meeting in Kottayam, Madan Mohan Malaviya — visiting Travancore on Madhavan’s invitation — had exhorted his audience to chant ‘Ramaya namah’. Led by Periyar and the atheist leader Sahodaran Ayyappan, many responded with precisely the opposite: ‘Ravanaya namah’.

Nevertheless, Periyar came together with Madhavan and other ideological rivals to play a noted role in the Vaikom Satyagraha, which entered its third stage after the death of one of its most intractable foes, Maharaja Moolam Thirunal Rama Varma, in August. His successor, Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma, was a boy, and power passed into the hands of a regent: Maharani Sethu Lakshmi Bayi.

The regent immediately released the 19 satyagrahis who had been jailed in April, while the campaign continued much as before. But now, the attention was on two jathas (marches) of caste Hindus that traversed the state in support of the movement — a triumph for Madhavan’s policy of allying with the dominant castes. A resolution calling for the opening of roads around temples was also introduced in Travancore’s legislature on 25 October 1924, and was defeated by a single vote.

The fourth phase began with Gandhi’s visit to the state in March 1925. He spoke to all parties but was only able to get the police to withdraw their barricades — in exchange for the satyagrahis promising not to enter the forbidden zones.

The final stage was a period of “waning interest” that lasted until November 1925, writes Jeffrey. By this point, the government had completed alternative roads near the temple that were open to the avarnas, while a few lanes remained closed to them. The last satyagrahi was withdrawn on 23 November.

The guru, the Mahatma and the Malayali Brahmana

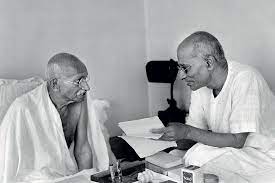

Does the swamiji speak English? No. Does the Mahatma speak Sanskrit? No. That’s how a well-known conversation between Gandhi and Narayana Guru began on 13 March 1925.

This interaction between the two came after a misunderstanding over the possibility of violence in the campaign the previous year. In June 1924, an Ezhava journalist reported an informal conversation with the guru, in which the latter had purportedly said, “the volunteers standing outside the barricades in heavy rains will serve no useful purpose…They should scale over the barricades and not only walk along the prohibited roads but enter all temples…It should be made practically impossible for anyone to practise untouchability.” Gandhians were alarmed, and the guru wrote to Gandhi to say that there had been misreporting and misunderstanding.

When the two met in March 1925, it was at Narayana Guru’s Sivagiri ashram, wrote Kottukoyikkal Velayudhan in Sreenarayanaguru Jeevithacharithram. Gandhi spoke in English, the guru in Sanskrit, and N. Kumaran translated. A few of their exchanges follow

Gandhi: Some say that a non-violent satyagraha will be useless and violence is needed to secure rights. What is the swami’s opinion?

Guru: I don’t think violence is good.

Gandhi: Do the Hindu dharmashastras prescribe violence?

Guru: It can be seen in the puranas that it’s necessary for kings and others, and they have used it. It may not be right for ordinary people.

Gandhi: Some are of the opinion that religious conversion is needed and that’s the true path to freedom. Would the swamiji agree?

Guru: It can be seen that people who’ve converted are gaining freedoms. When people see that, they can’t be blamed for saying religious conversion is good.

Gandhi: Does the swamiji think Hinduism is enough for the soul to attain moksha?

Guru: Other religions also have a path to moksha, don’t they?

The conversation continued in that vein. The references to conversion may be seen in the context of the situation in Travancore, where conversion to other religions such as Christianity removed the disabilities of untouchability, at least officially; an avarna who had become Christian could do much that was forbidden to his Hindu counterpart.

A few days before, at Vaikom, Gandhi had had another conversation the history books have recorded, with a Namboothiri Brahmana of the Indanthuruthi mana — the custodians of the Mahadeva temple. He was accompanied by others including Rajagopalachari, Mahadev Desai and the Nair leader Mannathu Padmanabhan.

When Gandhi questioned restrictions on avarnas using public roads, the Namboothiri replied that it was the fruit of their karma, and cited the long-held rights of the Brahmanas. He then asked Gandhi why he thought the avarnas were oppressed. When Gandhi made a comparison to Jallianwala Bagh, the Namboothiri asked if he were calling Shankaracharya a ‘Dyer’ — in Kerala, many of the laws regarding caste were codified in the mediaeval Shankarasmriti, a book traditionally attributed to Shankaracharya (believed to have been a Kerala Brahmana himself), although the consensus now is that it’s a much later work.

The argument went nowhere, with the Namboothiri resorting to silence when Gandhi tried to press him. It revealed just how inflexible orthodox attitudes continued to be, and that the anti-caste movement still had a long and difficult road ahead.

Aftermath

The tangible gains of the movement had been few, and it ended with a compromise after the government constructed a few new roads that avarnas could use without “polluting” the temple. A few lanes and of course, the temple itself, remained barred to them. More satyagrahas on the Vaikom model followed in the next few years, but bore little fruit; the avarnas seemed no closer to temple entry.

However, the Vaikom Satyagraha set in motion many forces that would go on to transform the politics of Travancore and the entire region of Kerala. Its leaders attained immense stature — Madhavan became a towering figure among his contemporaries and continued to be an indefatigable organiser, while others such as K. Kelappan and K.P. Kesava Menon — the president of the Kerala Pradesh Congress Committee and editor of Mathrubhumi — could mobilise their accrued prestige to revitalise the Congress in the wake of the Malabar Rebellion.

The eventual Temple Entry Proclamation of 1936 was the result of complex politics and the government led by the diwan, Sir C.P. Ramaswami Iyer, being alert to the dangers staring it in the face. Militant rhetoric was gaining popularity among disgruntled Ezhavas, while the community was also drifting closer to Christians and Muslims; in 1933, the representatives of 12 Christian, Muslim and Ezhava organisations formed the Joint Political Congress to boycott that year’s election and demand greater representation in the legislature and in government service. And above all, there was the looming threat of mass conversion, especially to Christianity, which haunted a government that desperately wanted to preserve Travancore’s ‘Hindu’ identity, Jeffrey wrote.

The rest of Kerala would take longer to follow suit, with avarnas only being granted entry to all temples after more satyagrahas and even after Independence.

As for T.K. Madhavan, an injury suffered during a later agitation — when he was following Narayana Guru’s directions to push forward forcefully if physically stopped — would continue to haunt him for the rest of his foreshortened life. His final illness struck him in 1930 when he was resting in the shade of almond trees at his home.

As his friend and occasional rival, the poet Kumaran Asan, once wrote, ‘Kaalam kuranja dinamenkilum arthadeergham‘. The days were short, but they were long with meaning.

Courtesy : The Print

Note: This news piece was originally published in theprint.com and used purely for non-profit/non-commercial purposes exclusively for Human Rights